Poverty and insufficient drug regulation expose Zimbabwe to HIV

Spread This News

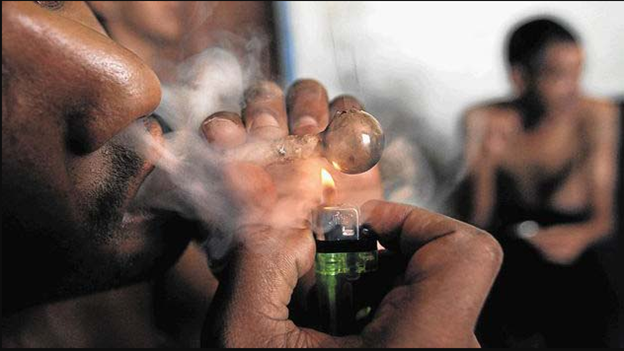

HARARE – Drug use continues to grow throughout Zimbabwe, particularly among people who are vulnerable to or who have already been diagnosed with HIV.

In many instances, people who use drugs (PWUD) who are living with HIV acquired the virus not through intravenous drug use, but through condom-less sex.

Though antiretroviral therapy (ART) allows people living with HIV (PLWH) to repress the virus and live healthy lives without worrying about transmission, habitual drug use has created numerous health issues, including dependencies that lead to treatment interruption or reduce treatment effectiveness.

Though Zimbabwe does not collect official data on drug use, in 2020, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) found that rising unemployment during the pandemic “likely” made those with the fewest resources more vulnerable to drug use as well as trafficking and cultivation to earn money.

In 2022, UNICEF noted that the pandemic’s strain on the mental health of young Zimbabweans contributed to an increase in drug use and sexual activity without using harm reduction methods such as condoms or pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Lack of Opportunities Drives Poverty, Drug Use, and HIV Vulnerability

Beyond drug use, poverty has also been cited as a major driver of HIV transmissions across Southern Africa, because it pushes people who are in financial precarity into survival sex work―but without the agency to demand that harm reduction be used or access to employ it themselves. Due to decades of gender inequality, women and young girls―who carry the heaviest HIV burden across sub-Saharan Africa―are especially vulnerable to the hazards of survival sex work.

Looking at statistics within Zimbabwe, the International Labour Organization found that in 2019, the country had a national unemployment rate of 7.4%, with an even higher rate among young women and men who were not actively pursuing education or training. Respectively, these gendered groups accounted for a 36.2% and 29.4% unemployment rate among all people younger than 35 years old. The significance of this data is that people within this age group represent 67.7% of Zimbabwe’s overall population.

With further pandemic-linked losses in financial opportunities, much younger PWUD in Zimbabwe have turned to gather at secret social spaces in residential areas―colloquially called “bases”―to use drugs or to sell items in order to purchase drugs. In recent years, codeine-laced cough syrup and crystal methamphetamine―or guka and mutoriro, as they are known locally to minimize detection by the police―have become the drugs of choice.

In many instances, teenage girls and young women without resources offer transactional sex in lieu of payment. But even without this exchange, Romio Matshazi, the CEO of Active Youth Zimbabwe, told TheBody that “some people who use drugs heavily mostly perform condomless sex while they are high, without knowing what’s happening around themselves.”

The Consequences of Dependency and Insufficient Treatment Options

Active Youth Zimbabwe is a drug treatment and rehabilitation organization that focuses on helping younger people escape dire circumstances. Matshazi noted that many of the people they try to help are often “unaware of the HIV status of their sexual partners, further increasing the risk of HIV transmission.” Research conducted by Active Use Zimbabwe notes that drug use is on the rise across the country, particularly among those between 11 and 18 years old. Given the association between drug use and sex―especially when crystal meth is involved, which is noted for increasing sexual desire and lowering inhibitions―the consequences are high.

For instance, though official data in Zimbabwe is sporadic, available statistics from 2018 found high rates of HIV diagnoses among people aged 15 to 24, especially young women, who accounted for 9,000 novel diagnoses, compared to young men, who accounted for 4,200. Without treatment, many PWUD who develop dependencies stay reliant upon drugs for much of their lives.

In an interview with TheBody, Thomas Gonese, 38, explained that heavy use interrupted his antiretroviral treatment (ART). Five years ago, while residing at a drug outlet, he said that h began using cough syrups. In Zimbabwe, cough syrup contains codeine. The brand-name version―Broncleer―has become especially popular in recent years. The Medicines Control Authority of Zimbabwe (MCAZ) prohibits the sale and use of Broncleer without a prescription. But it is often smuggled across borders from neighboring countries and easily purchased at corner stores or bases.

In 2020, for instance, a truck driver was apprehended while trying to smuggle 12,500 bottles of Broncleer cough syrup into the country. Though there have been previous police reports, the illegal trade continues. As a result, it is not uncommon to see brown bottles of Broncleer littering commercial sidewalks and alleys.

When taken as prescribed, in small doses, the codeine in this cough syrup has proven beneficial for pain management. But when used habitually, it has been known to trigger respiratory problems, brain damage, strain on the heart and liver, and dependency.

To date, Zimbabwe’s chronically underfunded health ministry has failed to address drug rehabilitation, while private institutions are too expensive for the majority to access. But even people who can afford private care have had to turn to public institutions since the pandemic, due to loss of resources. As a result, medical tourism―with people flying to other countries for care―has flourished over the past decade, with citizens who can afford the fees paying over $4 billion for care from 2011 to 2021.

That has not been an option for Zimbabwe’s young and poor. Instead, when the price of cough syrup recently surged from $4 a bottle to $7, many shifted gears toward less expensive options. Thomas Gonese told TheBody that he and his friends opted for crystal meth. He said that while using meth, he rarely used condoms during sex. After testing positive for HIV, he began treatment with ART, while continuing to use illicit drugs.

Over the course of three years, Gonese said, he stopped using ART twice due to his dependency and grief. The first treatment interruption occurred while he was grieving the death of his firstborn child; the second interruption followed a year later after his wife died. According to his friend, Ben―who asked that TheBody identify him by a different name―during this second interruption, Gonese became so sick that he ended up in the hospital.

A Need for Regulation

Gonese’s experience with ART-interruption–induced sickness is far from uncommon. As Alois Tandai―a nurse based in Masvingo who specializes in HIV treatment―explained to TheBody, PLWH who repeatedly stop treatment can develop viral resistance. When this happens, the HIV virus in one’s body can mutate and adapt to one’s ART regimen, rendering it ineffective. In these instances, a new and less resistant ART must be found, which, Tandai said, “is often very expensive and out of the reach of many people. Instead, they end up with health complications or even death.”

State institutions have failed to keep up with the rising number of people who are using opiates and methamphetamines. In this instance, it is an issue of the country’s underfunded health infrastructure and high medical staff turnover as well. Between 2021 and 2022, nearly 4,000 healthcare workers left the country for Europe, mainly the United Kingdom, in search of better wages and working conditions. And, as Active Youth Zimbabwe notes, “drug rehabilitation services are still limited in Zimbabwe.”

A number of nongovernmental organizations have started to assist federal efforts with harm reduction in hard-hit areas by providing anti-drug awareness campaigns, workshops, community dialogues, anti-drug social media campaigns, and church lectures.

However, the lack of a national blueprint for intervention and rehabilitation has slowed the fight. In 2021, for instance, after Anesha Brenda Gumbo was arrested for possession of 98 grams of crystal meth, his lawyer argued that under Zimbabwe’s Dangerous Drugs Act (chapter 15:02)―which controls the importation, exportation, production, possession, sale, distribution, and use of dangerous drugs―crystal meth is not listed or classified as a dangerous drug; therefore, he said, “it is not an offense to deal in or possess it.”

A year later, crystal meth was still unclassified. According to a statement obtained by the Zimbabwe Independent from Virginia Mabhiza―the Ministry of Justice’s permanent secretary―, this delay was caused despite the government knowing that it needed to classify crystal meth as a dangerous drug. As Mabhiza explained, “Before we make concrete steps on such key legal deliberations, we have to consult first with other relevant stakeholders.”

Though the hazards of crystal meth use are clear, without regulation, it is impossible for Zimbabwe to protect its citizens from the hazards of drugs or exploitation. And without financial opportunities, people who are vulnerable to drugs and HIV will remain caught in a cycle of poverty and poor health.

There are approximately 16 million people living in Zimbabwe. According to UNAIDS, more than 1.3 million of them are living with HIV. In other words, 1 in 12 people are living with the virus. But there has been progress. HIV transmissions have declined by 80% since the late 1990s. In October, the Ministry of Health announced that as of June 2022, the country had surpassed its UN 95-95-95 target (meaning 95% of people with HIV had been diagnosed, 95% of those diagnosed were in treatment, and 95% of those in treatment were virally suppressed) with a rate of 96-97-95.

However, if drug dependencies and poverty continue to interfere with the use of harm reduction and ART treatment, those gains will likely plateau if not recede.