Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

The BBC's Mary Harper writes about her experiences at Somali beauty parlors.

I was relaxing in a comfy chair when a woman came at me with a long, sharp knife.

That first time, I was terrified.

Now I am accustomed to ladies approaching me with blades. It is all in the name of beauty.

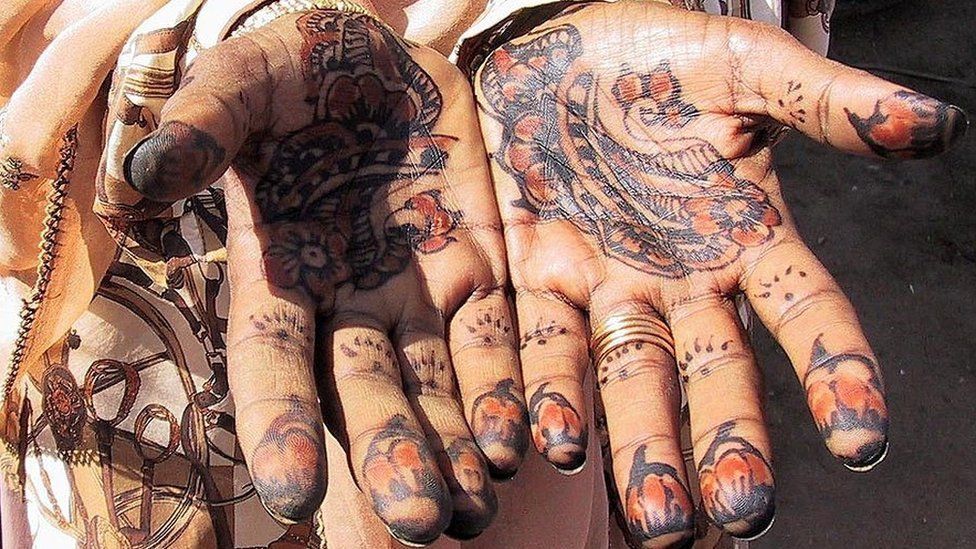

Carving knives are used in some beauty parlors to scrape the dried henna paste off legs, arms, and hands, revealing delicate, dainty patterns on the skin that slowly fade away with time.

Whenever I go to the Kenyan capital, Nairobi, my friend Suheyba meets me in the predominantly Somali neighborhood of Eastleigh - known as "Little Mogadishu". After a lunch of camel meat, we go for henna.

The last salon we went to was about the size of a cupboard, separated from the bustling street outside by nothing more than a ragged curtain.

Inside, everything feels different.

In communities where women are expected to cover up and keep quiet, beauty parlors are a place for them to breathe and throw off the trappings of their male-dominated societies.

Sometimes this happens quite literally. On a recent visit, a woman marched into the parlor and declared it was far too hot. She took off her veil, her long dress, her petticoats, and all manner of other undergarments including her bra.

Halal dating and cupcake chat

It is the same next door, in Somalia itself, where every woman is covered from head to toe. Plenty wear niqabs which cover the whole face except for the eyes.

Image source, Mary Harper

Image source, Mary Harper

Image caption, Mary has henna scraped off her feet

The first time I visited a Somali beauty salon, there was something strange about the woman who opened the door.

It took me a few seconds to register that she was not wearing a hijab, her luxuriant black hair flowing down below her shoulders.

"Oh, take that nonsense off," she said as soon as I went in, helping me to remove my headscarf and other garments.

When we got down to the bottom layer, a long underskirt, she gathered it up and stuffed it into my knickers so I could walk around without tripping over.

She took me into a room where women and girls lounged around in various states of undress.

Others wore skin-tight jeans and crop tops - usually hidden under their abayas, the long robes they wear in public.

I spent a lovely afternoon there, talking about halal dating, cupcakes, and how you have to have a baby pretty much every year if you did not want your husband to find a second wife. Plus, those annual babies should ideally be boys.

Men's hair dye

The first time I had henna applied in Somalia, the beautician produced a little yellow cardboard box. There was a photo on it of a smiling man with dark hair.

It was men's hair dye from Indonesia. She tipped it into the henna powder, stirred it in, and applied it to my white skin.

Image source, Mary Harper

Image source, Mary Harper

Image caption, Mary was not impressed with the jet-black designs

The result was jet-black designs that look great on Somali women's skin but stark and ferocious on mine. It took months to fade.

And then there is the self-declared republic of Somaliland. One of my favorite things to do when I am in the capital, Hargeisa, is to pile into a rickety taxi with a group of female friends and head for Bella Rosa Day Spa.

It was started by a Somali woman who decided to return home from Canada where she had lived for decades after fleeing the civil war.

It is staffed almost entirely by Kenyans. Many spent time working as beauticians in the Gulf.

Some have horror stories of physical and psychological abuse in Dubai and elsewhere. They say that although they are still far from home and the pay is worse, they prefer being in a Somali city.

I learn many things during my beauty salon chats. Therapists and their clients open windows into their lives - their marriages, insecurities, frustrations, and moments of joy.

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption, Henna is part of the culture of many communities in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East

In recent months, the conversation has shifted to politics when I visit my favorite beauty therapist in London.

She is Eritrean and has a tiny salon on a side street in the lively Brixton area.

She tells me how the previously harmonious Ethiopian and Eritrean diaspora in the UK has been torn apart by the war in Ethiopia's Tigray region in which Eritrean troops are involved. Former friends shun each other depending on their ethnicity.

Knife-wielding fury

But back to the ladies with the knives. Whenever they produce them, I am reminded of another knife-wielding Somali woman whose intent had nothing to do with beauty.

It happened after I interviewed her in the city of Bur'ao. She was sitting in a makeshift shelter in the livestock market stirring food in a big pot. In my report, I described her as poor.

When she heard my piece, she was furious. How dare I say she was poor?

Somalis are fantastically proud. And it's that pride that strikes me in the beauty parlors, where elaborate hairstyles and exquisite henna designs are created"

She went and found the person who had taken me around the market. When she met him, she drew out a long knife from under her robes and declared that she would use it to kill me if she saw me again.

It is the killings and the three decades of conflict that usually come to people's minds when they think of Somalia.

It is often described as the world's most dangerous country. A haven for pirates and suicide bombers.

It did not surprise me that that woman wanted to kill me because I described her as poor. Somalis are fantastically proud.

And it's that pride that strikes me in the beauty parlors, where elaborate hairstyles and exquisite henna designs are created - then largely hidden under headscarves and long robes.

I hope I will never meet the woman in the livestock market again and that the only knives that come anywhere near me are those used to reveal the beautiful patterns on my skin.

You may also be interested in:

- 'I want it to be normal for women to take photos'

- Mourning my friend, the dry cleaner of Mogadishu

- The ex-Islamist militant driving a school bus

- Somalia's frightening network of Islamist spies

From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

Listen on BBC Sounds, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service, or on Radio 4 on Thursdays at 11:00 and Saturdays at 11:30

he unit is staffed and managed entirely by women with full editorial independence and will produce stories for TV, radio and online media. Nasrin Mohamed Ibraham is Bilan’s Chief Editor.

UNDP Somalia