The conspiracy of silence about UK migration and it's terrible ‘Shangani Bag return’ consequences

Spread This News

It’s not many months ago since I found myself writing to the UK government on behalf of the diaspora community following en masse deportations of Zimbabweans. Some people had lived in the UK for all their adult lives, and many were approaching old age. Separation from family is such an excruciatingly painful process, that, for one who has not had such experiences, it’s pretty easy to trivialize it, and make a such humorous caricature of men with Shangani bags. However, the man with a Shangani bag is someone’s father, someone’s lover, brother, and so on.

I have had such traumatizing experiences of helplessly attempting to console “big men” breaking down, sobbing like little children, faced with deportation prospects. Former President Robert Mugabe warned about migration challenges, but what alternative did he provide the citizens? Many left the country because of his policies, and anti-opposition cruelty. Fewer people left the country during colonial rule than during Mugabe’s reign, and even greater numbers are leaving today due to his legacy, which leads, in essence, to the real reason for this article. Mugabe’s legacy has been the main “push factor” for population migration from Zimbabwe.

I recall around early 2000, a time before my emigration journey to the UK. There was only one theme that dominated discussions wherever you met people, whether in the ‘holy’ circles of churches, among those who enjoyed their pass time with “holy drink”, or even at workplaces. You would just hear that so and so has left for the UK; surprisingly they just left without warning, or a word, even to their close relatives.

I believe there were examples of some who left without informing their wives or children. It was a common occurrence to just discover in the morning, that a colleague has not turned up for work. I heard of many cases where some just abandoned company cars at the airport. They did not bother to hand over any work or materials which belonged to their employment. One would wonder whether it is just a Zimbabwean way of doing things to be so secretive; even when people are doing the same things (would sharing notes not increase prospects of success?). People are not even comfortable sharing information about their health conditions; simple things like blood pressure and diabetes, where you can learn ways to manage your conditions from each other.

What could be the reasons for this attitude? Some attribute this to spirituality and fear of witchcraft; some believe that talking or sharing jinxes your chances while some believe that people can betray your trust and phone the UK authorities to “grass” you about your pending arrival and about the falsehoods you intend to present as the reasons for your seeking asylum. Again, some just fear the embarrassment which comes with deportation in case they are refused entry.

This attitude of silence continues throughout the journey and settlement in the UK though, and surprisingly. On arrival, we were coached by those who came before, if you are that lucky to have someone so generous, in some cases unlucky, because some of the coaching and knowledge was extremely detrimental. We were taught to use false names to secure employment, and false documents were an easy reach, “just your pocket”.

RELATED:

- Anger as UK steps up Zim deportations; one fears brutal beating at Harare airport

- UK: Priti Patel’s deportations deal with Zimbabwe putting lives at risk

- Zimbabwean Quaker and activists fight deportation from the UK; claims life in danger if returned to Harare

- UK Home Minister Unapologetic For Deporting Zimbabweans

Some of the compatriots pretended to be from countries other than Zimbabwe, not sure why any other poor country in Africa could be a better association option than Zimbabwe. Meanwhile, Nigerians, Congolese, and many other nationals were traveling to buy Zimbabwean passports to come to the UK to claim Asylum.

Each fellow Zimbabwean you met pretended to have everything in order. No one would tell you about claiming asylum, but Home Office records show that an estimated 20,000 people from Zimbabwe claimed asylum in the UK at the beginning of the year 2000. Who are those 20k people then? Maybe they are not Zimbabweans, it could be other nationals who took advantage of the Zimbabwean political meltdown, because every Zimbabwean I met then, claimed they had work permits, or they were students at universities/colleges.

However, if they were students though, they must have been unique students. They never seemed to miss a work “shift” (as we called it), and they worked very long hours, contrary to UK law which only allows students to work 20 hours a week. If they really had work permits also, in early 2000 work permits were for higher skills jobs, why were these people working 60 hours a week in factories and care jobs? At what point did they work in their specialized fields which they got the permits for?

Fast forward 20 years later, the UK Home Office announces deportations of failed asylum seekers to Zimbabwe. You begin to hear of detentions and “on the run” stories about very close compatriots. Some eventually braved it and reached out to their communities for support, however, some chose to face deportation than to seek help and support from their communities, not sure if this is the wisest way of dealing with problems and challenges.

Even those who later came out to seek help, I would like to believe that their situations would not have reached the deportation stage if they had opened up and shared their problems with their communities in time. In Shona, they also say, “benzi bunza rakanaka” (meaning to say, everyone has the potential to give helpful advice, just ask, do not look down upon anyone). Many came to the UK through the asylum route, and there is nothing embarrassing about it. They have legitimized their stay and are now very productive UK citizens, and the government is very aware of that, hence the reason they have extended yet another opportunity to take more people from Africa. Zimbabwe is leading this latest exodus.

A new wave of movements to the UK has resumed since “Brexit” (a term used to describe UK withdrawal from the European Union). And compatriots are using again, the same “modus operandi”; everything is done quietly. Nothing was learned from the early 2000 movements. We hope not to have a repeat of the 2021 deportation lamentations. The current movements have taken a two-way process of “hushed tones”, an environment so dangerous for exploitation of each other.

Zimbabweans who have already settled in the UK have seized the opportunity to deal with the labor market deficit in the UK, a great idea, and as usual, we all do the same thing, but with cards close to our chests. Again, not sure if it’s induced by the same fears such as those of 20yrs ago, like witchcraft and so on. Society has a tendency to name their children after great events, I would not be surprised to hear of some youngsters called COS in a few months (Certificate of Sponsor, a document that I am also desperately looking for on behalf of my loved ones). Most people in Zimbabwe and other parts of Africa are looking for this golden document. Many are selling homes to purchase this document which is sold by prospective employers in the UK.

This document is supposed to be free to the employees under UK immigration law (1971 Immigration Act), hence its literal meaning of “certificate of sponsor”. It means the employer is the sponsor, the reason why the employer applies for the employment sponsor license from the Home Office. However, if you are Zimbabwean, you really understand, the “the nothing for free” statement. There is no need for much laboring with details around this unless you want to make more enemies than friends in my society. When you ask friends that run the care companies about these COSs, the information you get is so sketchy, even information to also register a similar business is not easily shared. We have coined a statement, “that’s a Zimbabwean way anyway”, so, is it surprising?

In Zimbabwe also, friends and relatives are busy running around chasing the COS quietly, they do not tell anyone, in case the witches catch the wind and jinx things as usual. The problem though, just as in early 2000, the episode does not go without victims. The pains and the joys of social media, it’s not regulated, you just wake up to the very traumatic wailing of victims without warning. Victims just pop up on your Facebook without discretional warning, it doesn’t matter your nervous disposition to handle such content. The secretive “opportunity environment” is the breeding and hunting ground for scammers. They maximize, asking for divine and ancestral spiritual intervention does not help once you have been duped.

Those who filter through the scamming risks also face huge challenges on arrival in the UK. Chief among the challenges is poor regulation of the migrants’ working environment, reportedly leading to visa renewal struggles. The UK Guardian recently reported concerns about rent arrears, homelessness, employment, and challenges of accessing medical services among the new migrant workers. The migrant workers seeking to extend or formalize their immigration are given a status called 3C while they wait for the Home Office to process their application.

The purpose of section 3C, 1971 Immigration Act leave, is to prevent a person who makes an in-time application to extend their leave from becoming an overstayer while awaiting a decision on that application and while any appeal or administrative review they are entitled to be pending (Home Office, 1971 Immigration Act). Although their right to work is protected, they, however, have no documents to evidence their status, which then creates challenges for employers and landlords. Employers are afraid of the increased penalties if they fail to conduct adequate immigration status checks in line with immigration policy changes from 2012. The changes have made it harder for anyone without documentary proof of their valid immigration status to access healthcare, benefits, driving licenses, bank accounts or mobile phone contracts.

The section 3C challenge is that it does not extend leave, where the application is made after the applicant’s current leave, has expired. The 3C leave application is also a complicated legal process, which requires expert legal applications, attracting substantial costs, and thereby presenting challenges for these migrant workers. We are already aware that most of our people migrate for low-income employment such as social care jobs, and other jobs which attract little local market demand due to the level of remuneration and conditions of service. This, therefore, compounded with migrant workers’ limited understanding of UK laws, and support networks, resulting in many failing to extend their visas within the required time frames, which then presents a wave of illegal migrants in the country.

There are also high risks associated with employer compliance issues that are not of the migrant workers’ own responsibility, such as rogue employers and agencies who are reportedly extortionately charging applicants exorbitant fees for the certificate of sponsors (COS), anecdotal reports are that charges are ranging from £5k-£10k. The law states that evidence that the person paid someone to provide the document, and that person was not authorized to accept such payments is grounds enough for withdrawal of the 3C leave. This is a situation in which the migrant workers are reportedly trapped, as they have to purchase these expensive COSs due to lack of choice induced by considerable pressure from lack of opportunities in the home countries, whether conscious or unconscious of the legal implications.

Furthermore, anecdotally, some recruiting employers are people who previously worked in the sectors, at operational levels, not even at middle management levels or just team leaders. They have serious challenges of skills and knowledge deficiencies of the policies, regulations, and organizational management in the industry. Again, because of the fear of “witchcraft”, these employers do not ask for help in time from the people closest to them. They then make some errors which result in the Home Office, and other regulatory bodies such as Care Quality Commission (CQC) revoking their operational licenses.

The Home Office gives the migrant workers just 60 days to find an alternative sponsor to issue them a new COS when the company they worked for has lost the license. This time frame to get another COS is very little, resulting in these employees becoming overstayers without valid visas. Bearing in mind that in that little window, getting another job requires a lot of procedures, such as references, and new criminal record checks, some employers prefer you to start by working for them before they can apply for a new COS, meanwhile your 60 days are ticking, no guarantee that they will apply for the COS for you.

Once you have become an overstayer, the UK immigration law is very punitive. You get banned for 10 years. To add salt to injury, these migrant workers would have uprooted their entire families, which impacts children attending schools. The unexpected legal changes and complexity caused problems for people from the Windrush generation, a group of black people from the Caribbeans, who came to deal with labor force shortages in the UK after the 2nd world. They ended up unable to prove their legal status in the UK, resulting in many of them getting deported, while those who remained were unable to work for decades, including their subsequent generations.

A Guardian newspaper report raises concerns that the new group of migrant workers is now facing similar difficulties because of this 3C status and this could lead to the same Windrush scandal outcomes. Who is prepared to go back to Zimbabwe after managing to escape the evils of poverty and the gallows of misrule? How many illegal immigrants are going to result from this so-called “opportunity”? The Windrush scandal is an understatement.

There are also widespread reports of revocation of sponsor licenses among many Zimbabwean community companies currently. Some companies are even losing their licenses before the people they recruited from Zimbabwe, and other parts of the world have managed to set off. Once this happens, the recruited employees’ visas are revoked, or refused, if they were not already granted/processed, despite the fact that they would have paid extortionate and illegal COS fees. This is causing unprecedented pain, heartbreak, and community disintegration.

In any company or work environment, there are likely to be disagreements naturally between employers and employees, however, unfortunately, when a sponsor license has been revoked in our communities, the suspicions between the employer and the employees become so complicated. Employers then suspect that those employees they had bad relations with reported them to the authorities. The entire community gets at loggerheads. It snaps all the already naturally strained fibers that hold communities together. But who facilitates the company which they work for to shut down, particularly when it impacts them as well?

Anyway, who knows, people make meaning from their experiences? It’s a complex working environment for both employers and employees. There is no data protection, some employers can just wake up on social media telling the whole wide world that they have lost their licenses, and their entire stock of staff have no work permits, the same applies to employees. Your work-related hardships are for public consumption on either party, employer, or employee, because of the community connectivity. Is this current work opportunity in the UK a real opportunity or just another Shangani bag heartbreak brewing? Will it create the same Windrush Scandal residual effects?

The new labor migrants from Zimbabwe are not only imagining a connection with the land of the UK and its white indigenous inhabitants on their arrival, they also have a deep reconnection fantasy with their brother, sister, uncle, and aunt who left them back home some few decades ago. To their unbelievable shock, however, the cultural distance that has grown between them over time is unimaginable. Africans in the UK, who settled earlier are now whiter culturally than the white themselves, so much that, even intra-family, there are massive gaps depending on who is acculturing faster than the other, is it father, mother, or children? They are not acculturating at the same rate.

The new African migrant worker is now living with his very close relatives, but distant by time and geography. In most cases you get temporary shelter while you wait to get on your feet and be independent; it does not matter if you are now in your 50s and set in your ways. You must adjust and comply with the norms and values of the people you live with. You have a flimsy familiarity with the problems of your relatives, and you kind of knew before you came. You always heard about their telephone calls reporting their “on and off” lifestyle, however, it’s a different ball game when it’s a live drama in your face. You are caught in the middle. It’s easy to become a victim of circumstances depending on which side of power in the house your actual relative is, wife or husband, in some cases children are even more powerful than their parents, they are now in their teens and twenties but living at home.

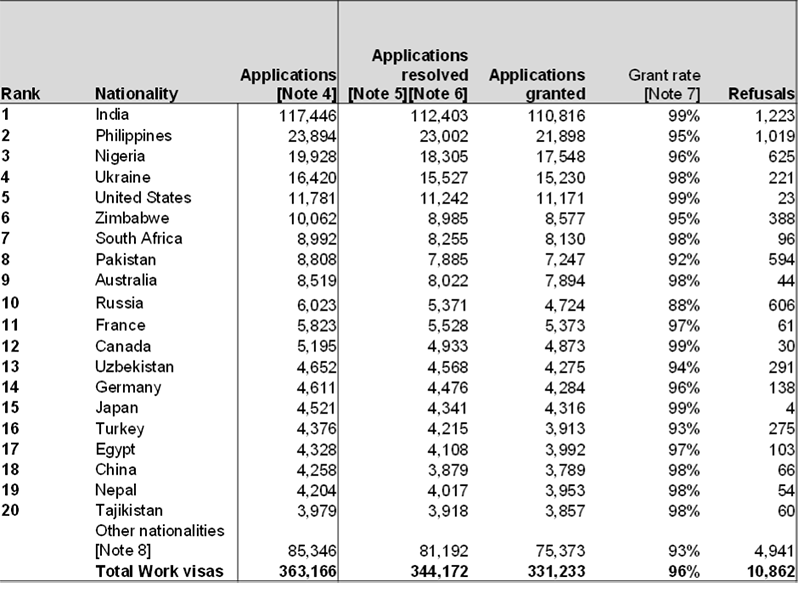

To put things into perspective about the level of current UK movements from Zimbabwe, table 1 contains the recent home office figures of the top 20 countries supplying the labor force to the UK. Nigeria, Zimbabwe, and South Africa are among the leading suppliers globally. Thanks to Brexit, UK’s labor market demands have shifted attention towards Africa. Despite Zimbabwe’s population size, it is just number 6 below the United States by a very small margin. Amongst the top 10 countries, Zimbabwe is the country with the smallest population but has very high figures of migrant workers leaving for UK.

Table 1. Work visa applications and outcomes, by nationality, in the year ending June 2022 – (Home Office Immigration Statistics).

What should be done by the Zimbabwe diaspora community to reduce the likelihood of the 2021 Shangani bag deportations repeating, and the potential “Windrush scandal” problem among our communities? You do not want to always be reactive, but proactive and address the problems before they happen. Currently, there is a huge leverage potential for negotiations with the UK government to push them to adjust some of their policies that impact the labor market participation of new sub-Saharan African (SSA) migrants.

The UK is clearly in dire labor force shortage, and anything that promotes sustainability of labor market participation of the new migrants is an open table invitation. Brexit has reinvigorated Britain’s re-engagement with the world beyond Europe, particularly its former colonies. The special relationship that Britain has with its former colonies was clearly neglected due to the UK’s EU membership which had supposedly diverted British attention solely to its near European neighbors.

The EU membership continued to hold back Britain’s stronger trading links with SSA. So, the sudden turn to recruiting large a number of workers from SSA is a clear demonstration of the recovery of this relationship. The UK Zimbabwean and its SSA diaspora community counterparts should now engage the government about the challenges faced by both black employers and employees in sustaining labor market engagement. The SSA governments should also join hands in these negotiations, then wait for just the deportation engagement of their citizens in return for bribes and aid.

Employers and employees should also make closer networks to deal with their challenges and have some internal or intra-community mechanisms for conflict resolution. There is no need to always resort to mainstream institutions, whose main agenda is large to sink your efforts. This is a lifetime opportunity that our communities can maximize if well managed. However, it can also be another source of community disintegration, pain, and heartbreak if not well managed.

Chris Goshomi is a Ph.D. Candidate in Politics and International Relations. His research focus is on sustainable labor market participation of generations of African descent in the UK.